The ‘9/11 Kids’ Are Grown Up. Their Grief Is Still Raw.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast / Photos Courtesy Karli Langone/Max Giaccone

For over 3,000 children who lost a parent on 9/11, the last 20 years have meant missing someone they maybe barely knew. Four “9/11 kids” talk about grief, memories, and moving on.

“A lot of my memories are jumbled of my dad. Prior to that night, unfortunately I remember not a whole lot,” Giaccone told The Daily Beast.

“I’m not sure if my mind is blocking it out. I remember good things. I remember my dad being there for every baseball game I had after school. I remember my dad tapping along to music as we drove to and from my baseball games. I remember him having a glass of wine on a Sunday night to wind down and get ready for the week. He usually did that in a dark room with Andrea Bocelli playing.”

A couple of years ago, Giaccone, now 30, watched an old home video of his dad. “I lost it. I hadn’t heard his voice in forever. It was incredibly difficult,” he recalls. “It is only through years of therapy and recognizing my own triggers that I got to a place a couple of weeks ago when I thought, ‘It’s time. I want to hear his voice.’”

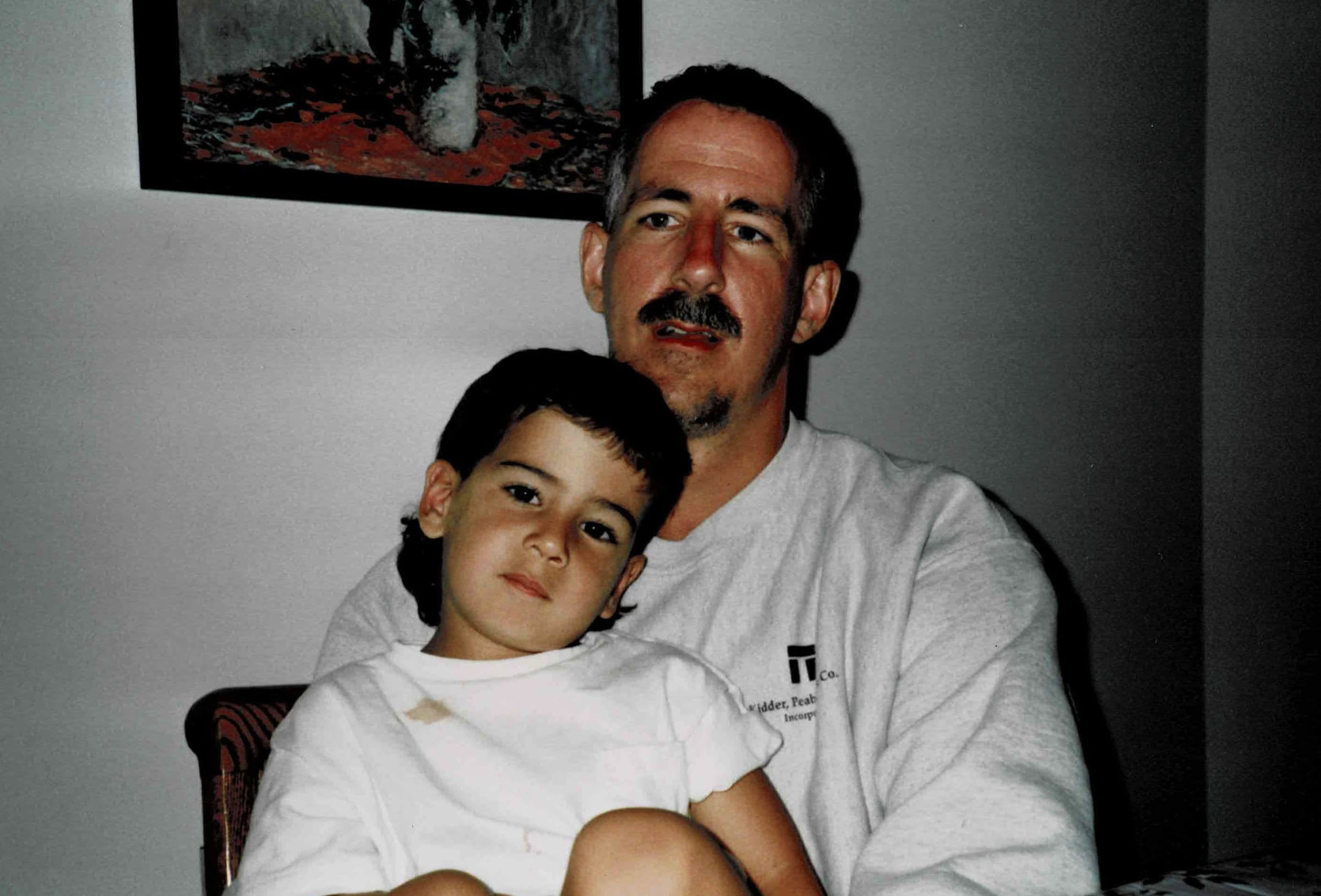

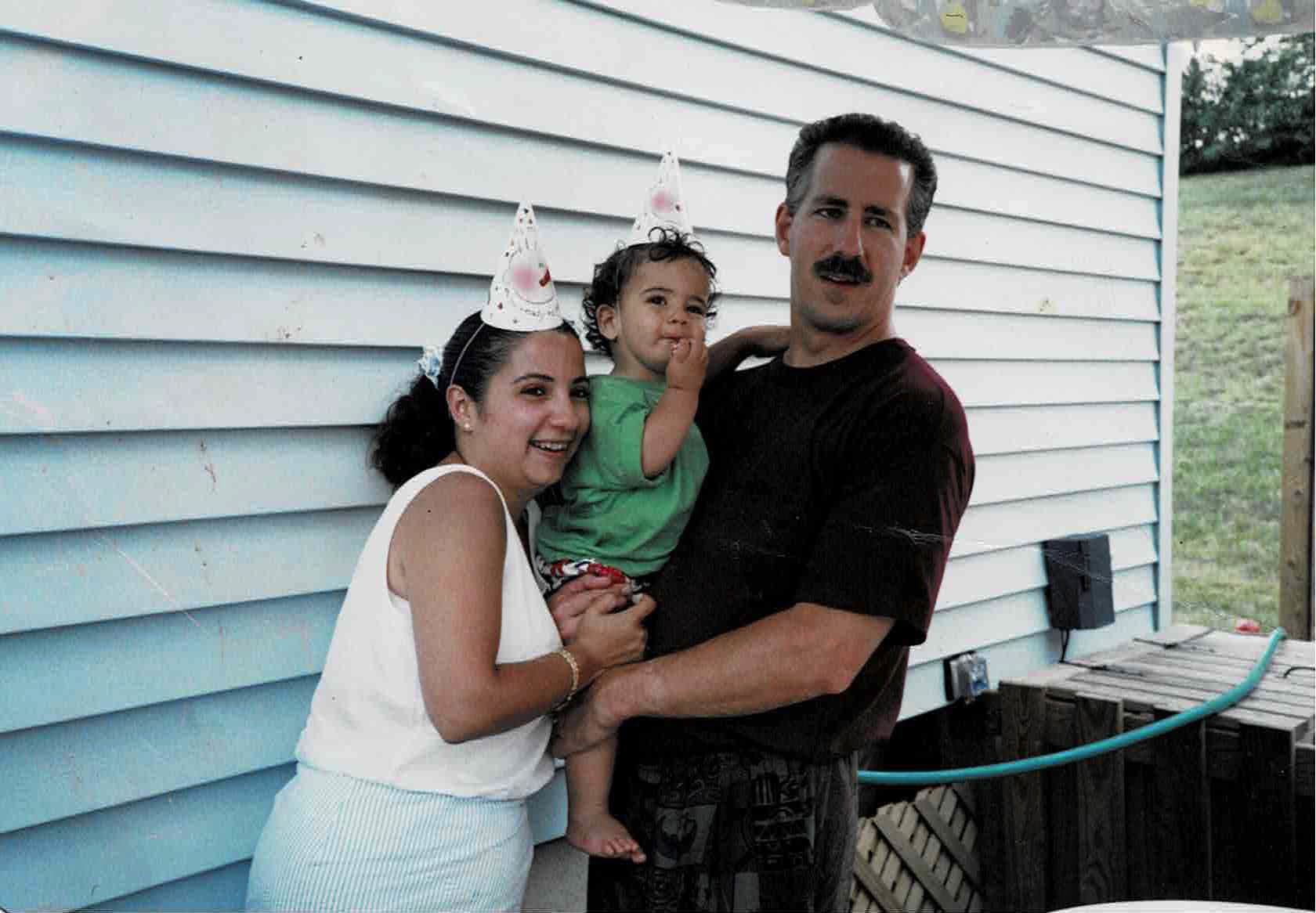

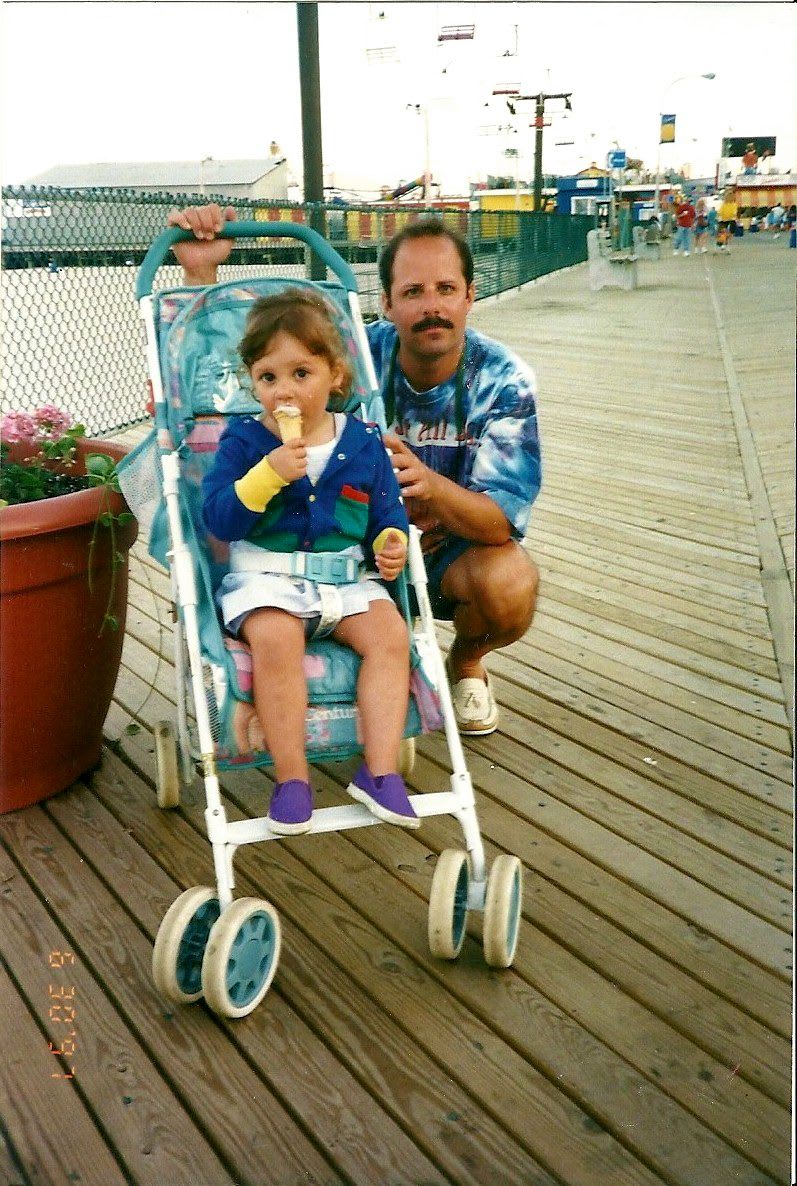

Courtesy Max Giaccone

Like many young children who lost parents on 9/11, Giaccone has lived more than double the time without their parent than they had with them. “I don’t remember the first five, six years of my life,” Giaccone told The Daily Beast. “I have pieces of memory. I only have a few years to go off. It’s hard to grieve something you don’t fully remember.”

Max was 10 when his father, Joseph M. Giaccone, was killed. The 43-year-old was a vice president at Cantor Fitzgerald’s Espeed division. He was married to Max’s mother Sondra, and Max is one of two surviving children. Now a freelance event producer who lives in New Jersey, Max recently finished digitizing the family’s home video collection.

“Going through the tapes has been good for me,” says Max. “It’s brought back memories, and put my mind back into places I haven’t gone to in a while. I keep thinking, ‘Oh I remember that,’ ‘Oh, I remember that little frame we had on the mantle.’

“I think two years ago when I first watched a video I was upset and not ready for it, but now I’m in a better state of mind. Don’t get me wrong. I cried my eyes out multiple times watching my dad recently on the tapes, but that was more out of happiness and joy.”

There are thousands like Max—3,051 to be exact, according toTerry Sears, president of the nonprofit Tuesday’s Children. She told The Daily Beast that the overwhelming majority of the parents lost were fathers. Tuesday’s Children was founded in the wake of 9/11 to support children and families who lost a loved one that day, and has expanded its scope over the years to support those who have lost loved ones due to military service, mass violence, or acts of terrorism.

“We started our focus on the children and then began programs for the surviving parent to gain their trust and make sure they were doing OK. Not for many years were they, and some not even to this day,” Sears told The Daily Beast. “It has been a particularly tough few weeks for 9/11 families and military families to see how Afghanistan ended, whatever they thought of the mission there. A lot of our members are feeling embarrassment, rage, frustration, and grief.”

“The public nature of 9/11 means it is in the news every day,” Sears added. “You’re a kid. You just want to be a kid, but you have this defining characteristic: you’re a 9/11 kid. It’s something many of the children didn’t want others to find out about them as they went forth in daily life as a roommate in college, at an internship, a job. They didn’t want others to hire them, or be their friend, because they felt sorry for them, or because they had this horrible thing happen to them.”

Karli Langone remembers her dad dropping her off at recitals.

“I remember being in his truck dropping off garbage at the garbage dump,” she told The Daily Beast. “I remember us going to a place where he got three hot dogs, and I got one, and he was able to finish three when I had not finished one. He worked all the time, and took care of us, but somehow, for any recital or class project, he made sure he was there.”

Karli was 5 when her father, Peter Langone, a 41-year-old firefighter, was killed. She has an older sister, Nikki, and mom Terri. Peter’s brother, Thomas Langone, a 39-year-old police officer, was also killed that day. Both brothers were volunteer firefighters with the Roslyn Rescue Fire Company. Karli, now 25, still lives in Roslyn, Long Island, with her mom.

On 9/11, Karli recalls being in kindergarten “in Miss Long’s class, and my mom and my aunt picked me up. I was definitely like, ‘This is weird. Why am I coming home from school?’ At that time I didn’t understand. I remember the news being on. You could see the smoke even from here. I remember us constantly being with each other, and dad never coming home. As time progressed, I think I just understood.”

Matt Wisniewski was 4 years old at the time.

“I recall my grandmother coming to pick me and my sister up from school,” he told the Daily Beast. “Beyond that, my memory is a bit fuzzy. I wasn’t told very much at the time.” Matt’s father, Alan, was an associate director of the Sandler O’Neill investment banking firm in the South Tower. He died at 47. He had been married to his wife Kathy for nine years, and had three children. Matt was the youngest.

Courtesy Matt Wisniewski

“I have old family photos and videos, but I don’t have many memories of my dad,” Matt told The Daily Beast. “Different stories have come from different family members. For me, the craziest thing was, when I was growing up, doctors or my dentist would tell me I was looking more and more like my dad, or sounding like him. It was weird having people tell me I was so similar to someone I hardly remembered or knew.”

On the morning of 9/11, Max Giaccone remembers his fifth grade teacher getting a phone call, “and I saw the expression on his face. He told me I needed to go to the school office. My mom was standing there. That’s when I found out. In the first couple of weeks anywhere between 10 and 25 people were in our house at any time. We had a good support system. I remember getting home: my grandmother quietly told my mom that Tower 2 had just fallen. I remember seeing that, and then being whisked upstairs.”

Amanda Tempesta recalls speaking to her father Anthony at his Cantor Fitzgerald desk on the 105th floor of the North Tower that morning; 9/11 is also her birthday. The night before she had asked her mom and dad to stay home to celebrate the day. She turned 7 in 2001; this Saturday she will turn 27. Her mother Ana Maria had called her husband that morning because she had discovered the front door of their New Jersey home was unusually unlocked. Anthony stayed on the phone as she searched the house, and told her he was sorry he was so far away.

Amanda and her brother Matthew had been fighting about something, and Amanda laughs that she “brattily tattle-taled” on her brother. Anthony spoke to Matthew, wished Amanda a happy birthday, and said that they would do something special later. Anthony’s mother also worked for Cantor Fitzgerald, but arrived late for work that morning, seeing the tragedy hideously unfold in front of her, and today is “alive and well and still with us,” says Amanda.

Later that day, Amanda made the hushed and tearful group of people gathered at the house laugh as she smashed her head into her birthday cake. The night of 9/11, Amanda recalls her mom telling her and Matthew that they didn’t know where their dad was; he could be hurt, confused, or dead, and continued to talk to her children sensitively and honestly as time went on.

“The 20th anniversary of 9/11 is being marked by the world, but it is not significant in and of itself for me,” Max says. “A number is just a number. This is my father we’re talking about. I miss him every day. I appreciate people still care. I think it’s also snuck up on me this year. I was in a really good place. Everything to do with Afghanistan brought a lot of old things to the surface. I am not a foreign policy expert. But 9/11 is the reason we were there. Whether it’s an Afghan person, an innocent bystander in all this, or a soldier, any innocent loss of life at this point is terrible.”

For Max, what he calls “this September feeling” creeps up on him in August “about how I am going to get to September 12th. As much as I appreciate people care, I sometimes wish it was a non-public event, and that I could have the day and weeks leading up to it to myself. Every time I go on the internet, 9/11 is just everywhere I turn. Missing my father is the same as last year. It will be the same 20 years from now. For me it’s just another year further away from the last time I saw my dad.”

Courtesy Max Giaccone

“Sometimes I get angry. Sometimes I don’t know what people are saying about 9/11,” Karli Langone says. “Sometimes people will post things, even if they were not directly affected by 9/11. I wish they didn’t. They don’t remember 9/11 every other day of the year. I do.”

“I feel grief is a never-ending thing”

“Sometimes words can fall short in expressing how people feel and their emotions. It’s hard to put into words how I felt,” Matt Wisniewski says of his grief and sense of loss. “As you go through life and become more mature, you begin to realize what you may have missed out on, or that you may have not been aware of when you were younger. I am very grateful to my mom and my family.

“They let me do a lot of things when I was growing up. My grandfather was very involved in my life, and a figure I was able to look up to. I try not to look back in grief, I try to look at things more in the way that my father would want me, my mom, and my sisters to be happy and do well. My dad and I shared a love of dancing. I did modern dance for a few years, and at my first dance concert when I was about 13 or 14, my mom bought me flowers, and afterwards cried and told me how proud of me she was.”

“We were not shy talking about my dad at home,” Karli Langone explains. “When I got into elementary school, I understood more. I feel grief is a never-ending thing. Sometimes it’s annoying that you can’t be private about it. I have friends whose parents have passed, and no one is going to say anything to them on, say, August 22nd. No one knows about it, no one will upset them. They can do things privately if they wish. That is something I wish I could do, to not be in the spotlight. But I can’t be mad people are honoring the day. It was a huge thing.”

“I was 5. Now I’m 25,” Karli says. “He wasn’t there for me graduating high school and college. I’ve lived 20 years without my dad. I have to say I am so fortunate to have my mom. She literally never stops going. She does everything, still to this day. She’s awesome. Without her, I would really be lost. It’s definitely been weird, but we made do with what we have.”

Some of the 9/11 kids describe clinging to the notion that their suddenly-vanished parent was not really dead.

“I felt a glimmer of hope after seeing an image of people walking over the bridge,” recalls Max Giaccone. “For a couple of weeks, I thought my dad might come back. There’s still some part of my brain that thinks he’s in a coma somewhere and will wake up one day. Obviously, I know that’s not factual. I’m sure a lot of people knew before I did that my dad was never coming home. I think as a 10-year-old boy you wonder if there’s a chance he is alive. There’s the ‘non-confirmedness’ of no body, not being able to fully know, having that sliver of hope to hold on to, and my mom finally having to come to me and saying to me, ‘He’s not coming home.’”

That 9/11 was and remains a global news event profoundly affected Max’s grieving process. “I don’t watch video of the buildings from that day. I’ve seen it all enough for it to be engrained in my psyche. Sometimes people just putting those things in articles makes me mad. I appreciate the argument that by showing history we are helping not repeat it, but I don’t know besides sensationalism what value it brings. I also try and stay away from are images of people jumping from the building. It has always been one of my biggest fears, and probably plays into my fear of heights.”

Max lived in Manhattan for four years until this past March, when he and his girlfriend moved back to Jersey because “living during lockdown in a one-bedroom apartment with a dog was too much.” He thinks he is still going through his grieving process.

“I think that grief is everywhere. I look for my dad in everything that I do. I think it’s turned from ‘bad grief’ to almost ‘good grief.’ Being able to look for my dad in situations that I love and enjoy doing has been good for me. Going to baseball games and seeing the Mets play, which is something we used to do together, is where I look for him. I look for him on his birthday when I have a glass of port in his honor.”

In the last few years, Max says he has “really struggled” with what kind of father Joseph was, “because I’ve been trying to figure out what person I am. I only have my mother’s memories to go off. She’s an amazing woman, and I am able to place a lot thanks to her, but watching these videos, the thing I saw was what a fucking awesome dad he was. Who the hell wants to sit at an 8-year-old’s baseball game? He did. He was there for me.”

The Monday after 9/11 Amanda Tempesta’s mom sat her and brother Matthew down for “the talk,” as Amanda calls it, where Amanda’s mom said that Anthony would not be coming home. As a young child, Amanda recalls not wanting to cry in front of her mother, wanting to be strong for her, wanting to be around her (even requesting that any friends’ sleepovers happened at their house).

She experienced what she called “the feeling,” which as an adult she remembers as akin to a panic attack. She would become upset seeing a cousin sitting on their dad’s lap, or seeing any father-daughter interaction, now cruelly denied to her. She recalls seeing a friend fighting with their mom, and Amanda saying they shouldn’t as her friend didn’t know how long her mom would be around. “For me, I lost my father first. The world trade center collapsing comes second,” Amanda says. “An odd truth is when I was younger there was a sense of excitement around the attention we got. I didn’t understand until I was older why we got that attention.”

Matt Wisniewski says missing his father “is a hard thing to explain or process through. I know he would have been proud of me at my graduations. Me, my sisters, and family try and go at least once a year to the 9/11 memorial. It’s very beautiful. I’m glad with what they have done with it. It’s a nice reminder to be able to see his name in the wall, and go into the museum and see pictures of me and him and with my sister.”

Since Matt was about 13, he has attended the Tuesday’s Children’s Project Common Bond, which was originally for children who lost fathers, mothers, and other family members in 9/11, but has since expanded to all those who have lost family members in other acts of terrorism.

Courtesy Max Giaccone

“It has been such an indispensable thing to grow up with,” Matt adds. “Knowing you could speak to others who have experienced trauma similar to which I have been experienced is something I am incredibly grateful for. It showed me the importance of being compassionate to one another, and how important it is to treasure every day of life I guess.”

“When my father died, I lost my best friend”

Watching the now-digitized family videos, Max Giaccone has been making emotional connections between past and present, and father and son.

“There was a hill where we grew up. One video shows him using one of those children’s picnic tables as a sledding luge for me and my sister. He could have said, ‘Go sled, I’ll sit here.’ No, he got in it. I think I share his characteristic of being a giant kid. On the sled, he says, ‘Here’s to the world’s stupidest home videos.’ That’s something I would do.”

Max has found other videos marking joyful occasions like the Christmases of 1991 and 1992. “All I want to do is hand my Christmas presents to my father, and my mom says, ‘Of course, the favorite gets all his presents first,’” Max says. “He was my favorite. No slight to my mom, she will always be number one. But when my father died, I lost my best friend. I lost the guy I looked up to immensely. I lost the guy I looked to for guidance. I was a stubborn little brat, but he didn’t berate me. He didn’t talk down to me. I questioned from time to time who he was asa person, and would I have liked him. I think after watching all this it’s a resounding ‘Yes.’”

Karli Langone says her dad isn’t an unknown presence. “We still talk about him, and what he would say. It doubly sucks that his brother, my uncle, died that day too. That’s two amazing guys, just gone. My uncle was also an amazing dad.”

Karli feels that people close to her who have passed are always with her. “With my dad, sometimes if some object moves or falls, I think, ‘Ah, that’s dad.’ It was about 17 or 18 years before I went to the 9/11 site for the first time. I don’t feel my dad is there. I know he’s with me.”

Like so many 9/11 families, the Giaccones never received remains of their loved one. “There was no closure besides the death certificate,” Max says. “No casket or ashes. Sometimes it’s hard for the brain to close that gap. Around 10 years ago, we were asked if we wanted to submit a new DNA sample. I said yes, and my mom I think was hesitant. It’s hard. For me, it would be nice to have something. But it’s such a weird statement to say I would want part of my dad’s arm. Sorry, I don’t mean to sound gruesome. I don’t think I will be able to answer the question properly until if that day comes.”

The Langone family also never received remains. “Since I never got to see my dad’s body or anything like that—they never found him—it’s like, I know he’s with me,” Karli says. “I feel like I made my peace. Sometimes, I think maybe he did survive, maybe he’s living his life with a new family. It’s wishful thinking. I know he’s not. If they did find something of him it would be really awesome to have a proper funeral. Even though we had one, it would be nice, but I’m not holding on to that.”

“People say they are sorry my dad ‘passed away.’ No, he was murdered,” adds Max Giaccone. “For a while when I was young, I couldn’t direct my anger about that anywhere. I was angry at everyone. You take normal teenage angst and you top it with your father being murdered in public viewing, and it’s a bit of a recipe for disaster.

“I was an angry asshole for those years,” Max adds.“I definitely think 9/11, and how he died, had lot to do with that. Twenty years on, we are still having to ask the government to do the right thing about Saudi Arabia.” (After pressure from victims’ families, the Biden administration has signaled it will release some documents in relation to connections of the Saudi government to 15 of the 9/11 hijackers who were Saudi. Victims’ families continue to pursue a long-running lawsuit against Saudi Arabia.)

Amanda Tempesta recalls being known as a 9/11 kid at school, sometimes hurtfully so like when she won the role of Dorothy in a production of The Wizard of Oz, and getting teased by other kids about her father’s death. Growing up has brought an evolving emotional awareness and knowledge. She says she tries to not let what happened define her, while recognizing the centrality of her father’s death in her life.

As with the other children, Amanda sees grief as a long-time, evolving thing in her life, accentuated at moments when she would have liked her father to have been with her. Two years ago, her boyfriend’s sister got engaged, and listening to her dad speak warm words was “super hard.”

Her dad Anthony loved music (the Allman Brothers were a favorite band), and played bass in a number of bands. He would come home from work, and Amanda and Matthew would wrestle with him. Amanda would sneak downstairs to listen to him practice with bandmates in the basement. He would blast music when mowing the lawn. One Halloween, all the kids in the neighborhood were invited to the Tempestas’ firepit, where Anthony regaled everyone with ghost stories. Like her dad, Amanda loves being outside.

Her dad always told her to look at the moon, and when Amanda does she feels close to him. She associates the color green with him—from the color of his favorite beer bottle, Becks, to his favorite football team, the New York Jets. Whenever she hears an Allman Brothers song, she thinks of him. She got “the chills” when she felt his presence while visiting the 9/11 Museum. When she makes decisions, Amanda, a freelance event producer based in Los Angeles, thinks about what her father would advise, and would want for her. Like Karli, Amanda feels her dad is with her.

“I want to be able to cherish his memory”

Music also connects Max Giaccone and his father. “I have my dad’s playlist: Steely Dan, Andrea Bocelli, Pink Floyd, and David Gray. Music has been one of my greatest emotional inputs and outputs. Pre-COVID, there was a time I was going to one concert a week, especially in Manhattan. I’m pretty much an open book, and I very much appreciate people pouring their hearts out on stage.”

For Matt Wisniewski, although 20 years has passed, “in so many ways it seems like it hasn’t. Seeing the memorial every year brings back memories and feelings in ways that are very reflective. The 20th anniversary is a bit of a reminder that my dad is unfortunately not around, but a positive reminder that had he been around I think he would be happy for what his family had done. I want to cherish his memory.”

The impact of being the child of someone slain on 9/11 extends to some of their future careers and professional lives.

“There have been 9/11 kids who have joined the military, and those who lost a loved one on 9/11 who mentor Gold Star family members,” says Terry Sears of Tuesday’s Children. “It’s the ripple effect of 9/11. Some kids may have gone into finance like their parent did, or peace-building, or conflict resolution.”

Matt is studying global affairs, and may work in the security or intelligence fields. “Twenty years on, I would tell my dad… that I love him, and that me, my sisters and my mom love him,” Matt adds. “We hope he is proud of us, and we all miss him so much every day.”

Like other 9/11 kids, Max missed his dad at certain milestones. “It was there when we celebrated my 30th birthday in Washington, D.C., and went to the Mets-Nationals game. It was there at my high school and college graduations. He was a fucking awesome dad. My mom always engrained into me that I could have a shitty dad for my entire life, but I had a really great one for 10 years. When she said that, I felt like saying, ‘I don’t care, I want my dad back.’ As I’ve gotten older, I think ‘Yeah, I could have had a terrible dad for my whole life, but I got 10 really great years.’”

Karli Langone says there isn’t anything she would like to say to her dad as the 20th anniversary approaches. “I know he’s here. On the anniversary every year we go to his firehouse, and the local firehouse here in Roslyn.” Last year, Karli’s boyfriend came with the family. “We were talking about my dad. My boyfriend got stung by a bee. I laughed and said, ‘That’s my dad giving you a little warning.’ I always say my boyfriend has it easy. He only has to deal with my mom.”

Her mother has always done “a great job” making Amanda Tempesta’s birthday the priority on the day itself, with “quiet time” built in to remember Anthony too. This year, the 20th anniversary will see a significant family gathering, meaning Amanda spending the day for the first time in New York itself.

“My mom always told me, ‘We’re going to celebrate his life rather than mourn his death,’ and that has really carried us through this last 20 years,” she says. “On one of the anniversaries in the first five years, mom was playing music in the house in the morning, and my grandmother, her mom, said, ‘Shouldn’t it be quiet?’ My mother said, ‘No. This is exactly what Anthony would want.’ That’s so true. I can’t remember a time in the house when music wasn’t playing.”

Max Giaccone seeks to honor his dad in his day-to-day life. “I remember being 8 or 9 and having Thanksgiving dinner at a nice New York restaurant,” he recalls. “We left, and I watched my dad hand our leftover food to someone living on the street. My dad said, ‘There are people less fortunate than us, and we do what we can.’ When I lived in Manhattan, I did the same thing. I do things I think he would have been proud of, and done himself.”

His father’s death has “100 percent shaped my own views around death and mortality,” adds Max. “I’m 30, my dad died when he was 43. I do my best to take on every day. I don’t succeed every time. But I do that knowing it could all end tomorrow. Last year, my mom had a brain tumor removed. Thankfully it’s all good now, but it was incredibly scary. I hate the whole cliché, but it reinforced you should live every day like it’s your last. I’m excited to be a dad one day, and if and when that happens, I’ll try and do what my mom did and let my child live their own life. As well as my dad, I owe so much to her.”

For the 20th anniversary, Max plans to be on the field for the pre-game tribute at the Mets-Yankees game at Citi Field—“somewhere I know my dad would be with me if he were here.” He will likely have “a few Black and Tans,” Max’s dad’s favorite drink.

Max is quiet when asked what he would say to his father now. “I have no idea. I look at my life as three different time periods: With Dad, Grieving Dad, and Without Dad. Maybe, ‘I miss you.’ That’s what I would say. That is what I feel.” Max pauses, and sighs. “I miss you.”