20 YEARS ON, CHILDREN OF 9/11 GRIEVE

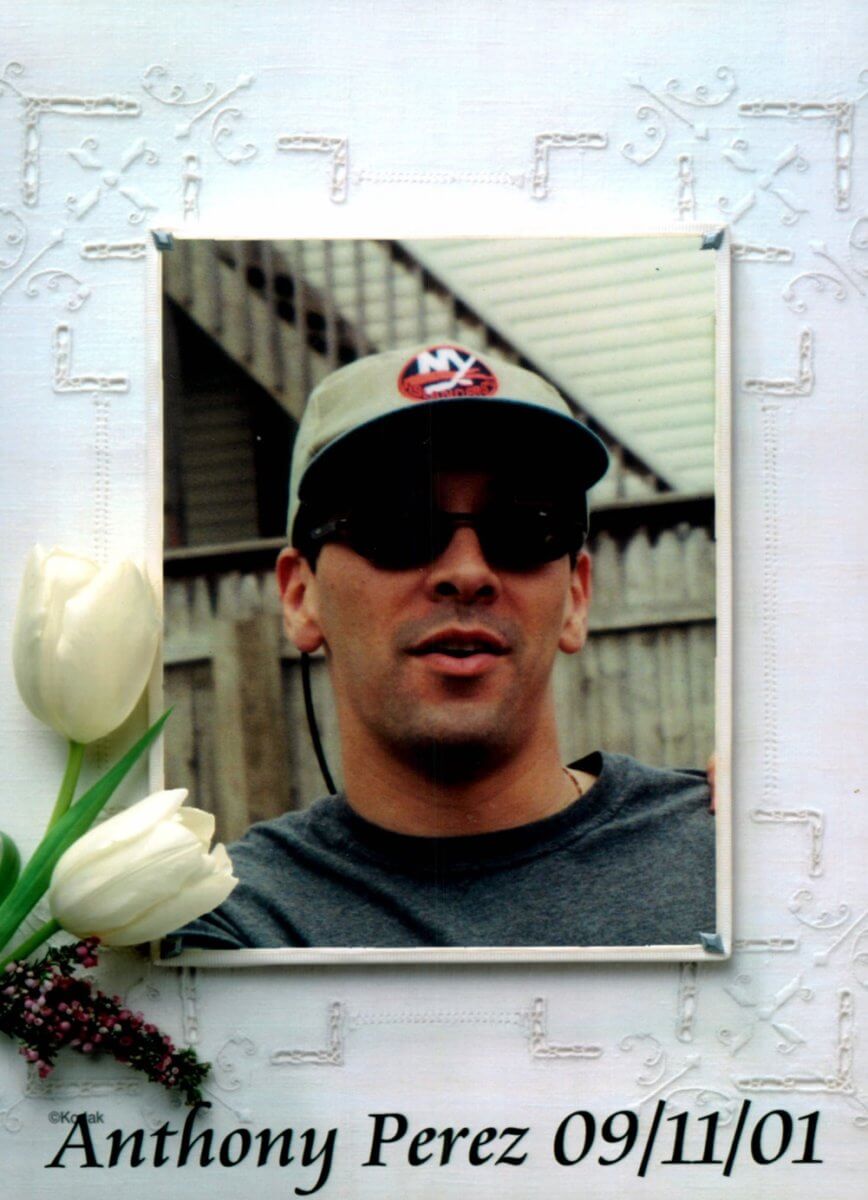

Anthony Perez was killed in the 9/11 attacks, leaving behind three children, including daughter Olivia Vilardi-Perez. Perez was one of more than 600 Cantor Fitzgerald employees who died that day.

Voices 9/11 Living Memorial

Olivia Vilardi-Perez signs her name just like her father, Anthony.

Anthony died on 9/11, when Vilardi-Perez was ten years old, one of more than 600 Cantor Fitzgerald employees working on the top floors of the north tower that morning. Years later, in college, Vilardi-Perez decided to get his signature tattooed.

“I gave the tattoo artist the signature off of his will, which was morbid enough as it is,” she said. “And he’s like, alright, I just need you to sign this paperwork. So I’m signing, and he goes ‘You understand you sign your name just like your father, right?’”

“It was very special, very weird.”

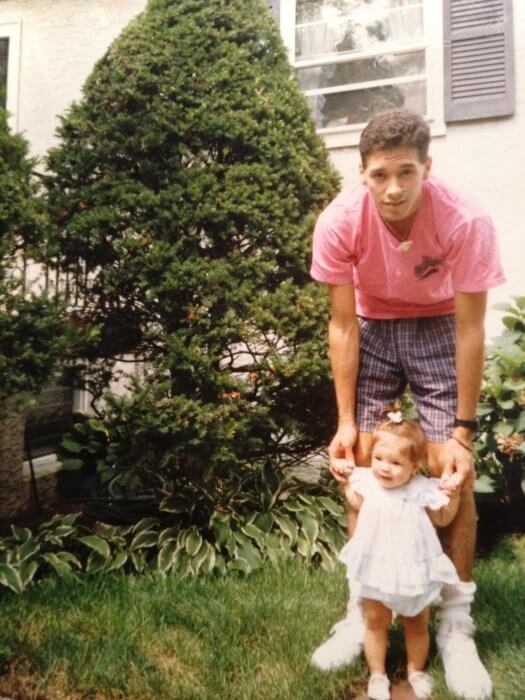

Olivia Vilardi-Perez was ten when her father, Anthony Perez, died in the 9/11 attacks. As an adult, she sees his selflessness and sense of humor in herself.

Olivia Vilardi-Perez was ten when her father, Anthony Perez, died in the 9/11 attacks. As an adult, she sees his selflessness and sense of humor in herself.

Photo: Olivia Vilardi Perez

It took years for Vilardi-Perez to get comfortable talking about her father, she said. In the aftermath of his death, she felt like she had to be the “rock” of the family, trying to stay calm and strong when her relatives were struggling.

“My uncle was getting married September 1, 2002,” she said. “I was supposed to walk down the aisle with my dad. The day of the wedding, my uncle was really struggling with that. I just felt the need to be the rock. I didn’t want to bring my dad up to anyone because it would make them upset, and I’d just feel upset when other people were crying or experiencing pain.”

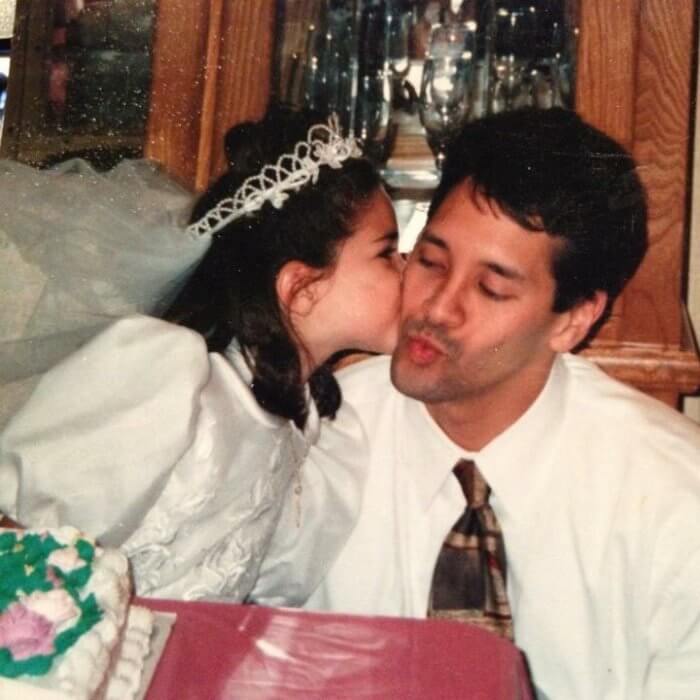

Anthony Perez was a huge “Star Wars” fan — something his daughter Olivia says he passed on to she and her brother.

Anthony Perez was a huge “Star Wars” fan — something his daughter Olivia says he passed on to she and her brother.

Voices 9/11 Living Memorial

Anthony and Vilardi-Perez’s mother weren’t married, and she lived primarily with her mother, spending some weekends with her father, stepmother, and two half-siblings. She was old enough when he passed to remember him, but young enough that those memories are hazy.

“Twenty years later, sometimes, you’re stuck wondering if it’s a real memory, if it’s a dream, if it’s something you made up to feel closer to him,” she said. “There are a few things I know about my dad. My dad loved video games, which he 100 percent has passed on to me. He loved ‘Star Wars,’ which he passed on to my brother and I. And he was just a jokester.”

Hearing stories about him as an adult, she said, is special. They’re not the kinds of stories friends and family would have told to her as a child, and they reveal parts of him she doesn’t think she would have appreciated as a kid, including parts of him she sees reflected in herself.

Olivia Vilardi Perez

Olivia Vilardi Perez

Now a high school science teacher, Vilardi-Perez said she’s always been the kind of person to put herself second to help other people, something her father was always doing. When someone is having a hard time, she’ll do anything to make them laugh.

“To hear the love that he felt for me, I don’t think I can explain the gravity of that,” she said. “It’s always nice to hear the lovely stories, but when things were bad for him, his main concerns were me and his children. It just goes to show you how great of a person he truly, truly was.”

The only person in her school who had lost a parent on 9/11, Vilardi-Perez was frustrated by the way people treated her – like she was fragile.

She got involved with Tuesday’s Children, a nonprofit organization founded in 2001 to support children and families who lost someone on 9/11. Even now, she’s still meeting new people through the organization, making connections with those who have experienced the same grief.

Sara Wingerath-Schlanger, senior program director at Tuesday’s Children, is still working to expand the mentorship program the organization has implemented to match grieving family members with someone who could help them through their loss long-term.

The average age of children of victims on 9/11 was eight or nine, Wingerath-Schlanger said, so they’ve served a wide range of ages as those children grew up and needed support. Enrollment increased especially on the fifth and tenth anniversaries, she said.

“No matter how old you were, if you were a child, you will re-grieve,” she said. “At different milestones, at different developmental stages. The big ones, like graduation and walking down the aisle, and the small ones like I’m walking down the street and I smell my dad’s cologne.”

Of the nearly 3,000 people who died on 9/11, 266 were Brooklyn residents. In the two decades since the attacks, first responders and those who worked at Ground Zero in the weeks and months following have continued to get sick and pass away from health conditions they developed on the site.

Tuesday’s Children was founded to support children and families of 9/11 victims, but has since expanded its mission to include children of first responders and soldiers who have died in the years since the attacks.

Tuesday’s Children was founded to support children and families of 9/11 victims, but has since expanded its mission to include children of first responders and soldiers who have died in the years since the attacks.

Tuesday’s Children

Many children were too young on 9/11 to remember the parent they lost. 108 women who lost partners that day were pregnant, and their children never met their fathers.

“Some kids feel like, ‘I was so little, I don’t have memories, or I was born after,’” Wingerath-Schlanger said. “And how does that make them feel, and how do they walk through this world figuring that out. And those that have memories and are able to say to themselves ‘I can feel the void.’”

Vilardi-Perez and her younger sister struggled with their memories of Anthony.

“I think her and I held resentment toward each other for too long,” she said. “I resented her because she lived with him. I didn’t live with him. And she resented me because I had the memory.”

The physical distance between Vilardi-Perez and her father means that a lot of her memories with him were in the small moments they shared together.

“We were watching a movie, the movie ‘Face/Off,’ and he’d be like, ‘Don’t look, don’t look, it’s gory!’” she said. “And he’d put his hand over my eyes, but leave just that little crack that if I just wanted to look, I could. But I don’t do gore. I never looked.”

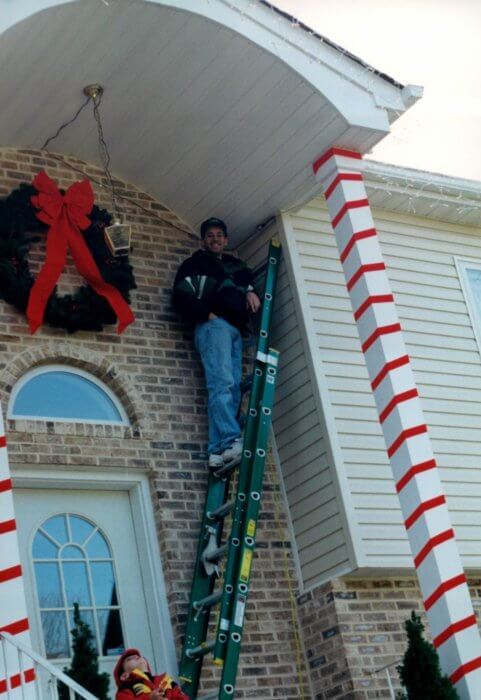

Anthony Perez, a father of three, decorates his Long Island home for Christmas. Perez died on 9/11, but his legacy of selflessness and laughter lives on in his children.

Anthony Perez, a father of three, decorates his Long Island home for Christmas. Perez died on 9/11, but his legacy of selflessness and laughter lives on in his children.

Voices 9/11 Living Memorial

Grieving her father isn’t linear. Every year, the anniversary is “an impossible grip around your heart, around your throat,” she said. Daily life got easier, but milestones – even the bad ones — are still difficult.

“I went through a really tough breakup recently, and I just remember saying ‘My dad would kill him. No doubt about it, my dad would kill him,’” she said. “He would buy me a drink, or he would help me, or he would guide me.”

Some of her best friends lost fathers who were firefighters, she said, and the firehouse door is always open when they need support.

“I am extremely envious of that,” she said. “I wish I had something like that. My father was never recovered, I don’t even have a gravesite. It is an alienating feeling knowing that I don’t necessarily have what they have in terms of memories or protection or guidance or father-like figures who just want to look after you.”

She pours that grief and the long journey through it into teaching, she said. Every year she starts out telling her students about her father’s death and the way she struggled through it. She’s upfront about her mental health and the help she needed as she got older.

“I have students who face horrible things, that no child should ever have to face,” she said. “And to have a teacher standing in front of them, who, I’m not going to say I’m fine, but I’m doing OK — who can make it through that, I think that’s a really important thing.”